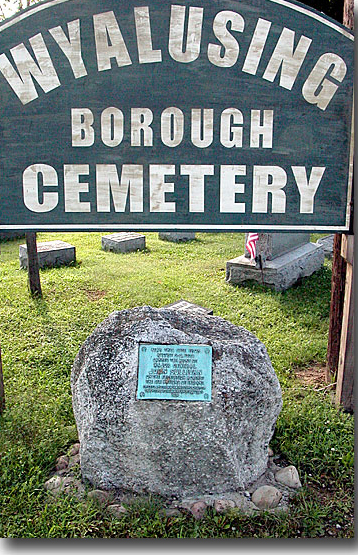

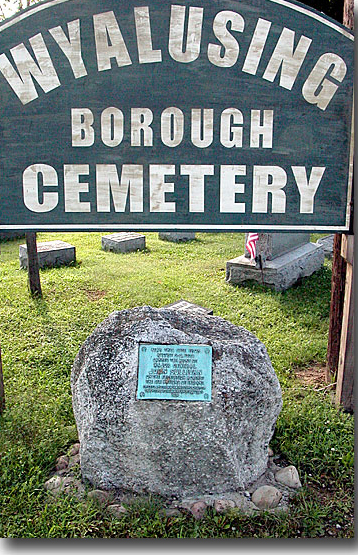

Remembering Sullivan's March through

Region 225 Years Ago - by Pete Hardenstine - 7/29/2004

Wyalusing Rocket, Wyalusing, PA

In the spring of 1779, George Washington faced a dilemma.

While his Continental

Army kept watch over the main British force based in New York City, he was

forced to deal with the Indian and Tory threat to his rear.

On July 3, 1778,

an enemy force of approximately 1,000 Iroquois and Tories under the command of

Major John Butler culminated a summer of terror along the North Branch of the

Susquehanna River with an assault on the fertile Wyoming Valley.

The Wyoming

Valley Massacre claimed an estimated 160 to 320 lives

Washington’s solution

was to split his force, sending nearly a third of his tiny army on a punitive

raid into Iroquois country.

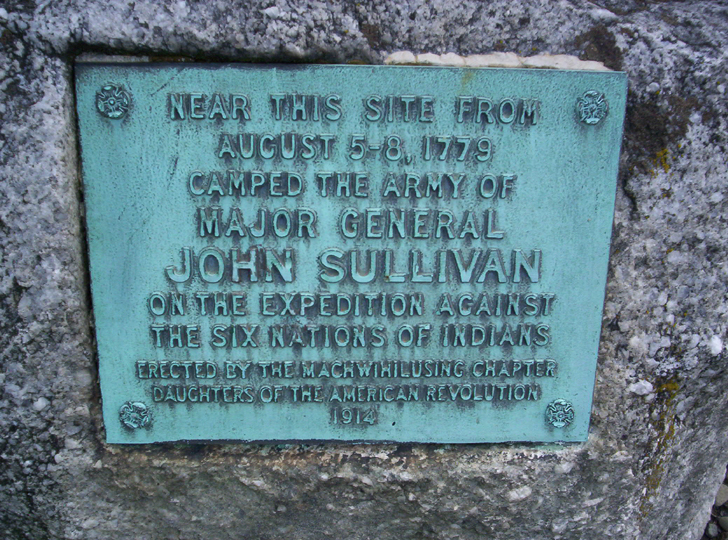

The expedition, under the command of Gen. John

Sullivan, left its mark on Wyoming and Bradford counties as well as the Finger

Lakes region where the force waged a scorched-earth attack against the Iroquois

homeland.

Sullivan’s March began in Wilkes-Barre on July 31, 1779—225 years

ago.

Susquehanna River

Wyalusing Rocks Lookout on Left

Along Route Taken by Sullivan's March

Source: Aerial Photograph Taken by Lyle Rockwell

November 12, 2010

Frontier under Siege

In the summer of 1778, the British

army, which had spent the previous winter encamped in Philadelphia, marched

across New Jersey to return to New York.

A hard-fought battle with

Washington’s army at Monmouth, NJ, during the march convinced the British

leadership that the Continental army was dramatically improved despite its hard

winter at Valley Forge.

With its main force bottled up in New York, the

British government sought to exploit a perceived Patriot weakness.

The

frontier to Washington’s rear was vulnerable to Indian raids, especially in the

northern Susquehanna River valley.

From its base in Fort Niagara, the British

encouraged the Iroquois Confederation to assault the vulnerable

settlements.

At the least, the Indian raids would slow the flow of foodstuffs

from the rich agricultural country to Washington’s army.

Urged to assault

people of “every age, sex and condition,” the Iroquois were willing allies of

the British.

As early as January 1778, the Indian threat became obvious in

what is now Bradford County.

Lemuel Fitch of Standing Stone was kidnapped

from his home that month and eventually died in captivity near Niagara.

At

Wyalusing, Amos York was taken captive in February, and Nathan Kingsley was

kidnapped in March.

In late March, Col. Dorrance and a force of 150 men

arrived from the Wyoming Valley to evacuate the settlers in the Wyalusing

area.

On May 20, a large Indian raid struck Wysox.

In June, a

force of 400 Indians and 400 Tories under Butler departed Tioga, the current

site of Athens, and headed downriver with its sights set on the Wyoming

Valley.

This group was reinforced by 200 Seneca warriors near the mouth of

Bowman’s Creek.

On June 30, the raiders fought a skirmish with a party

from Fort Jenkins.

On July 3, Butler demanded the surrender of all forts,

Continental soldiers and stores in the Valley.

A Patriot force instead

moved out to engage the enemy, but was routed.

Many of the captives were

brutally murdered in captivity by the Iroquois leader Queen Esther.

In the

aftermath, Butler’s Indians claimed taking 227 scalps, while Col. Nathan Denison

of the Connecticut militia reported 301 dead.

While Butler and his main force

returned victorious upriver on July 8, the last of the settlers in the Wyoming

Valley headed for safety by July 18.

In September, Col. Thomas Hartley

and 200 men led a raid from Fort Muncy up the Sheshequin Trail to take the fight

to the Indians.

After a skirmish near Canton, Hartley reached current day

Ulster where he destroyed Queen Esther’s village.

Retiring down the

Susquehanna, Hartley fought off an assault on Indian Hill on Sept. 29. He lost

four who were killed and had 10 soldiers injured in the

attack.

The Plan

With his rear, including his vital supply

sources, threatened, Washington decided to act against the Indian and Tory

threat.

Early in 1779, he developed a plan to take the fight to the Iroquois

and, if all went well, force the British at Niagara to use their vital supplies

to keep their Indian allies over the coming winter.

Giving the assignment to

Gen. Sullivan, a veteran commander from New Hampshire, Washington’s orders were

clear.

“The expedition you are appointed to command is directed against the

hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and

adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of

their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as

possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and

preventing their planting more…”

Sullivan was to gather 11 regiments at

Easton, march across the Poconos to Wilkes-Barre and move up the Susquehanna to

Tioga.

Meanwhile, in upstate New York, Gen. James Clinton was to bring five

regiments downriver from Otsego Lake (modern day Cooperstown) and meet

Sullivan’s main force at Tioga.

Out west, a single regiment under Col.

Daniel Broadhead was to advance from Fort Pitt up the Allegheny River and, if

possible, to meet up with Sullivan’s force.

In all, nearly a third of

Washington’s army would be detached for the expedition.

Sullivan arrived

at Easton on May 7, but the logistics of gathering and supplying such a large

force on a wilderness march forced a lengthy delay.

It wasn’t until June 23,

when a road had been completed over the Poconos, that Sullivan’s force departed

Easton for Wilkes-Barre.

Sullivan’s March

On July 31,

Sullivan was finally ready.

A force of 2,300 men, eight artillery pieces,

1,200 pack horses, approximately 800 cattle and 120 boats pushed off from

Wilkes-Barre.

Col. Thomas Proctor commanded the flotilla of boats.

Three

brigades, commanded by generals Edward Hand, William Maxwell and Enoch Poor,

made up the force, along with Proctor’s artillery regiment that included two

six-pounder cannon, four three-pounders and a pair of howitzers.

The

Pennsylvanians, under Hand, was the vanguard for the advance along the east bank

of the Susquehanna, usually staying a mile ahead of the main body.

Maxwell’s

New Jersey brigade advanced along the right flank, while Poor’s brigade of New

Hampshiremen and Massachusettsmen held the left flank.

A small group of 60

men under Capt. William Gifford advanced up the west side of the river.

The

large force, encumbered by its huge supply train, moved slowly up the

river.

By Aug. 3, it reached the mouth of the Tunkhannock Creek. On Aug.

4, it arrived at the Vanderlip and Williamson farms near current day Black

Walnut.